Ageless in the raw

If the landscape contains the spirit of the place, in a way this spirit is also linked to the identity of the observer. This notion has become increasingly evident because my connection with places has the tone of consciousness, of the feeling that accompanies me and is part of the memory and history of any person's wanderings.

In 2022 I began working in my new studio in a small village. Looking back at the paintings from that year, it is clear that they started to absorb the influence of the surrounding landscape. This region is marked by dense forests and a raw, wild nature, visible in the rocks that break through the earth on the mountain tops. It is a place that strongly engages the senses: a vegetal mantle of plants adapted to rooting in stony soil; an intense, sharp light that heightens colors and forms, making them appear almost carved in metal.

Many elements shaped my attraction to this geography, but above all, the sense of familiarity that comes from my ancestors, who settled there and raised their family. When I was younger, I did not feel particularly connected to the region, but over time that relationship changed. Today, it feels like home—a family place. The link to the past becomes tangible when I sense, in the surrounding landscape, a comfort and a feeling of belonging that I do not experience anywhere else.

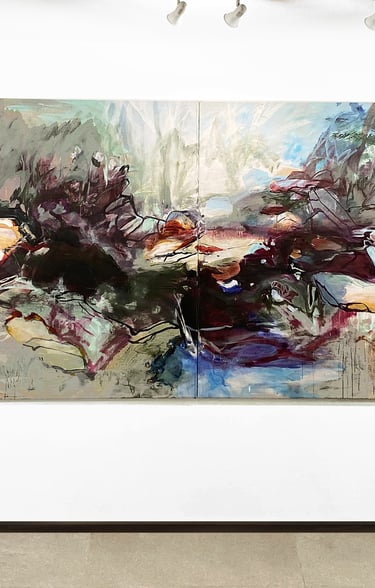

Working there led to unexpected developments in my practice. I realized how permeable my work was to the place itself. One of the first changes was a need to work on a larger scale—to feel physically immersed in the painting, in the same way I felt immersed while walking through the surrounding landscape. At that time, I had a group of canvases from previous phases, which I decided to reuse by working on their backs, made of raw cotton fabric. Many works began to have two faces, front and back, which immediately introduced a new dimension. Raw canvas demands a different approach and allows the paint to be absorbed like paper. This made it possible to use charcoal and Indian ink alongside acrylic paint, creating a bridge with earlier works on paper.

Not everything in these paintings was entirely new. There is never a clear border when beginning a new series. Connections and influences from earlier periods remained visible, and traces of previous works could still be recognized.

Even with new tones and directions, these paintings were supported by earlier experiences, giving me the confidence to explore new perspectives. This shift also reflected changes in my way of living: moving away from constant noise, allowing more time for reflection, stillness, and deep immersion in painting.

I usually work in series because a theme rarely resolves itself in a single piece. Ideas need time to mature, and during that process I move between several works at once—often seven or eight simultaneously—which creates continuity. When a series begins to feel exhausted, it means I have found new motivations or another way of expressing myself. Even so, strong links often remain between different series.

In the case of Ageless in the Raw, the earliest sketches already contain references to much older works dating back to 2015. Those earlier pieces can be seen as the foundation of what later emerged, as they were also influenced by long walks through the landscape and by my growing habit of spending short periods of time in this place. What happened was not a rupture or a revolution, but a transition—like a new skin that forms with a change of season or a new phase of life. A bridge was being built between past experience and present work, between what I had learned about representing landscape and what I wished to preserve about perception, consciousness, and the subjective way of seeing shaped by my own sensibility.

Each place in nature carries its own vital force. This energy leaves a mark on the landscape that varies from location to location. It is difficult to describe precisely, yet it becomes recognizable as a whole—something we instinctively identify as “that place.” This underlying matrix turns into a symbol through which the landscape can be understood. It emerges from the organization of reality itself: textures and colors, the relative position of things, the particular qualities of each element, the smells, the intensity of light on surfaces, the roughness of the ground, and the color of the sky.

In Ageless in the Raw, the symbols that interested me were representations of primordial elements: air, fire, earth, and water. Wherever I looked, I encountered them in multiple forms and variations, with great plasticity. What I found both unsettling and fascinating was the realization that everything is composed of basic elements arranged in specific ways and constantly evolving. In a simple sense, this cosmic dynamic shaped the focus and contours of my aesthetic interest—the inner pulse of the landscape.

What I observed was a scene in continuous transformation, rooted in a distant past and likely to endure even beyond the disappearance of the human species. From my perspective, it was compelling to witness what I think of as the “metamorphosis of the pseudo-eternal.” Despite appearances of stillness or inertia, energy was always present. Immobility was an illusion: at another level, there was constant movement and change, revealing the action of an organizing force that has been at work for as long as time itself, its imprint embedded in every particle of the landscape.

My expectations of opening a new line of work were fulfilled as a new series began to take shape. There was no doubt that the context in which I found myself was the driving force behind it. A significant shift was taking place, and I felt compelled to focus on the dialogue between the primordial elements of the landscape and the remaining human traces from the past—such as the ruins of old houses and mountain shelters. For me, these shelters embodied a lingering nomadic spirit within human habits, even in a culture where people once lived most of their lives in the same place. They also symbolized the traveler’s spirit, since these structures, often left with their doors open, served as refuges for walkers. Standing at the threshold of one of these shelters and imagining the many different lives that had passed through them, I projected onto their rough stone walls the curiosity of the solitary traveler seeking comfort in the landscape.

The interior of the country is a very different universe from the coastline, where most of the population lives and where infrastructure is concentrated. The territory where I now found myself felt semi-abandoned, marked by demographic emptiness and a lack of visible civilizational activity. Yet it was precisely there that silence could be found—where background noise settles and reality can be perceived from new angles. The beauty and diversity of the geography invited deeper observation and a more intimate communion with the natural world. Impressions were vivid and deeply etched into the senses. The slow rhythm of time in this region intensified these sensations and created the conditions for learning a new way of seeing.

When attention is directed toward consciousness and the energy transmitted by what is observed, perception becomes sharper and new ideas begin to emerge. This process brought a different tone to my work, allowing me to engage with reality in another way. It made me aware of nature’s creative force and of the intelligible information it offers—information that can be transformed into material for expression. Painting became a way of translating complex impressions of a three-dimensional world into two-dimensional images, guided by intuition and freedom of gesture. I was also struck by how the senses absorbed this constant flow of information and how memory reshaped it into a language that gives meaning to experience.

Immersion in a hyper-real environment—dense with unfamiliar stimuli—combined with a clear and attentive mental state, acted as an amplifier of sensation. The result was a vivid clarity that activated the imagination in multiple directions, leaving the feeling that reality contains far more layers than we usually perceive. This idea became central to the Ageless in the Raw series: the world as a dynamic overlap of layers, constantly mixing through an internal osmosis. The raw, exposed landscape—largely stripped of human presence—highlighted an absence that deeply affected me.

My response to this void was to intensify the dramatic charge of the landscape, emphasizing its mythical dimension. I began to imagine telluric forces imprisoned within the primordial elements—beings that, although invisible, seemed to express themselves through shadows and subtle signs: a cluster of trees along a riverbank, the crunch of rocks underfoot, the dancing flames of a forest fire, or the roar of water flowing over polished stones, resembling whispers or voices. I interpreted the organization and vitality of nature as the work of a supra-real force, operating on another level of existence. This imaginative reading carried a symbolic charge rooted in human memory and ancient instincts, addressing existential anxieties and primal fears. In the absence of people, I felt driven to read meaning into every element of the landscape, as if shaped by an invisible sculptor. It felt like the only way to explain such balance and vitality—qualities that always seemed to prevail over human intervention.

The relationship between ruins—especially the mountain shelters—and dominant elements of the landscape such as rivers, mountains, forests, and sunlight formed a dialogue between humanity and nature, between what is temporary and what endures, between the ageless and the ephemeral.

As traces of the past continued to fade, I felt as though I was witnessing the twilight of an era. Ruins were everywhere. At a certain point, I felt compelled to draw on the remaining walls, covered in patina, fungi, and lichens, stained with clay tones and limestone textures. I placed paintings among the rubble to see whether their colors resonated with the chromatic mixtures shaped by time. I sketched walls overtaken by thorny plants and imagined these places when they were still inhabited—when smoke rose from chimneys and daily life filled the space.

This led me to focus on the lingering marks of human presence: broken tables, rusted tools, agricultural objects. I knocked on the doors of the few houses still inhabited, collected stories, and photographed old images. I listened to accounts of people who were no longer alive and gained insight into the harshness of their lives and their resilience. Gradually, a stylized figure began to form in my mind—an absent character: caretaker of the land, father, beekeeper, companion to animals, explorer. This figure accompanied me on my walks and, on a subconscious level, seemed to explain the land to me. A narrative emerged, woven from photographs, memories, and stories shared by the remaining inhabitants.

Mountain shelters were scattered across the landscape, often appearing in striking locations with wide views over the surrounding terrain. Some could still be entered, revealing traces of their former use and prompting reflection on the hands that built them in such remote conditions. I first noticed these structures while walking near watercourses and gradually learned that they served as temporary shelters for people working land far from their villages. Over time, they became for me powerful symbols of absence—a way to represent the disappearance of people from the landscape.

In the paintings of the Ageless in the Raw series, these shelters appear in stylized forms, embedded in rock or engulfed by vegetation. They embody memories distilled from conversations and fragments of the past, and they stand as symbols of the fleeting nature of human presence when confronted with the slow, enduring transformations of the natural world. Ultimately, nature remains the governing force—the one that absorbs all things back into the oldest and most “raw” process of existence.